This article was published in Il Manifesto on 22 October 2006.

Gramsci torna in Italia grazie alla reinterpretazione della sua opera compiuta dai teorici critici degli «studi culturali». Una lezione a Bologna della filosofa di origine indiana Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

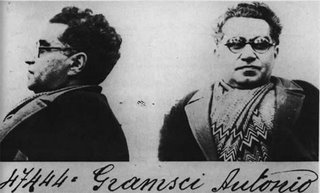

Cosa rappresenta l'eredità di Antonio Gramsci per il pensiero politico del presente? Forse non è esagerato dire che oggi la lettura di Gramsci ha raggiunto un minimo storico nel Nord del mondo, e quando pure Gramsci viene letto è spesso per dichiarare la sua irrelevanza. Basta citare il titolo di un libro pubblicato l'anno scorso in Canada, Gramsci is Dead di Richard Day, o consultare il sito di un altro studioso molto più acuto, Jon Beasley Murray che attualmente sta scrivendo un libro intotolato Posthegemony e sostiene che il concetto di egemonia non è adeguato per analizzare la presente organizzazione del potere (posthegemony.blogspot.com).

Il ritorno in Italia

In Italia è palese che una parte dell'ultima generazione politica, quella etichettata molto problematicamente come no-global , lavora con una cassetta di attrezzi concettuali assai diversa da quella gramsciana: sussunzione reale invece di egemonia, moltitudine invece di subalterno, cognitariato invece di intellettuale organico, esodo invece di rivoluzione passiva, postfordismo invece di fordismo. È sufficiente però soffermarsi su questi ultimi due concetti (ricordando che il prefisso «post» indica non solo una rottura ma anche una continuità) per rendersi conto che l'eredità di Gramsci non è totalmente dispersa in Italia. Questo in aggiunta al fatto che il suo pensiero sta tornando nel suo paese d'origine tramite flussi transnazionali, soprattutto quelli associati alla diffusione dei cosiddetti studi postcoloniali. Segnale eloquente di questo flusso di ritorno è l'invito rivolto a Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, nota non solo come una dei principali esponenti degli studi postcoloniali nel mondo ma anche come una pensatrice femminista di rilievo, a parlare di «Gramsci nella storia del presente» la scorsa settimana a Bologna. Il seminario, organizzato dall'Istituto Gramsci dell'Emilia Romagna, la rivista Studi culturali , il dipartimento di politica, istituzioni, storia dell'università di Bologna e il Johns Hopkins University Sais Center, è nato proprio dalla volontà di riconoscere il proficuo influsso che il pensiero gramsciano ha esercitato sugli studi postcoloniali. A partire dai primi anni Settanta, gli scritti di Gramsci sono infatti diventati un punto di riferimento importante per i teorici critici che hanno subìto l'esperienza del colonialismo, sia quelli che hanno traslocato nelle metropoli occidentali sia quelli che vivono tutt'ora nel Sud del mondo. Esempi importanti sono, a questo riguardo i lavori di Stuart Hall, un giamaicano emigrato nel Regno Unito, fra i protagonisti dei primi studi culturali che ha reinterpretato la categoria di egemonia per riconcepire le relazioni razziali-etniche di potere e lanciare una delle prime critiche al neoliberismo nella Gran Bretagna di Thatcher. Esemplare è al proposito l'assunzione del pensiero di Gramsci nella «Subaltern Studies Collectiv»e di Calcutta, di cui la Spivak ha fatto parte per tanti anni, per studiare il ruolo del contadino indiano e di altre figure sociali subalterne nela lotta anticoloniale. L'invito a Spivak perché parlasse di Gramsci a Bologna da un lato suona come un riconoscimento del confronto avviato dal Sud del mondo con questo pensatore italiano. Dall'altro lato però, essendo Spivak una docente prestigiosa della altrettanto prestigiosa Columbia University di New York, registra la tendenza tutta italiana ad importare con un certo ritardo le mode del mondo intellettuale statunitense. Infatti Spivak, consapevole di questa dinamica, ha approfittato dell'invito per intraprendere un detour tramite gli scritti di Gramsci ed esplorare quello che lei descrive come il suo «totale doppio legame individuale»: una condizione dovuta al fatto di non essere solo docente in una delle università più potenti del mondo ma di avere anche lavorato negli ultimi vent'anni come insegnante di «bimbi subalterni» in alcune scuole delle provincie piu povere del Bengala.

L'intellettuale e il subalterno

A partire dai saggi di Gramsci sull'istruzione - che enfatizzano non solo le potenzialità della scuola nella «guerra di posizione» contro le élite, ma anche l'esigenza di instaurare una certa disciplina nell'alunno tramite lezioni in latino e greco - Spivak struttura il suo intervento sulla memoria personale della sua esperienza in Bengala, per poi lanciare una critica alle iniziative volte a migliorare la situazione nel Sud globale tramite aggiustamenti top-down , dall'alto in basso: il «paternalismo autoimmune» o «l'imprenditorialità morale» delle Ong, così come gli sforzi di personalità «eccellenti» quali il premio Nobel per l'economai Joseph Stiglitz, che cercano di ridesignare il Washington consensus . Secondo Spivak ciò che è assente in queste iniziative è precisamente ciò che Gramsci le ha insegnato: come «ripensare l'interfaccia epistemica tra l'intelletuale e il subalterno», o come agire politicamente nel Sud «senza sparire nell'etico». La posta in gioco per Spivak non è solo quella di una istruzione radicale (sviluppata sulla scorta di Gramsci dal noto pedagogo brasiliano Paolo Freire), ma un'indagine su come «l'imaginazione può creare una storia dell'impossible, costruendo altri presenti per contestare il mio». Oppure, per ricordare il suo elegante sommario di quanto ha imparato da Gramsci: «come imparare ad imparare da sotto». Come può l'intellettuale convincere il subalterno invece di constringerlo, essendo lo spazio fra i due pieno di interpreti? È questa la domanda che Spivak affronta tramite la lettura di Gramsci, proponendo una risposta in tre momenti: l'aula, la lingua, il genere. Per quanto riguarda il primo, è palese che la Spivak non propone quello che Dipesh Chakrabarty, nel suo Provicializzare l'Europa (Meltemi), definisce postcolonialismo pedagogico: una politica che cerca di trasformare il subalterno in un obbediente cittadino dello stato moderno. Anzi, dato che il subalterno è già formalmente cittadino di uno stato moderno ma escluso dai processi non solo giuridici, la sfida è di lavorare con il subalterno per accedere ad uno spazio politico in cui egli può interrompere la narrativa dominante della globalizzazione. Per fare questo però non è abbastanza insegnare nell'aula del subalterno. È anche necessario istruire gli istruttori, nonché, aggiunge Spivak ricordando implicitamente il suo impegno alla Columbia, istruire le élite. A proposito della lingua, e premettendo che Gramsci non sarebbe oggi tra coloro interessati ad accedere ai circuiti globali dominanti con l'aiuto di un interprete, è solo necessario ricordare il suo interesse per i dialetti italiani. Lo sforzo epistemico di contro-globalizzazione, sostiene Spivak, non è empiricamente globale. In relazione al genere, Spivak insiste sul bisogno di andare oltre un femminismo recriminatorio - come quello di Teresa De Lauretis quando sostiene che Gramsci avrebbe usato le due donne della sua vita. Il contatto fra il femminismo e Gramsci sta piuttosto nel nesso fra agency e soggettività e, per Spivak, coinvolge una politica molta pragmatica che fa tutt'uno con la sua lotta di insegnante nel Bengala per tenere le bambine nella sua classe.

Tra nostalgia e rimozione

Tutto questo dimostra che Spivak non lavora per un ritorno a mo' di «restaurazione» di Gramsci, né in Italia né altrove. Quello che le interessa è piuttosto la lezione di Gramsci e la sua eredità. Come sappiamo dal Nietzsche di Sull'utilità e il danno della storia per la vita, il tentativo di dichiarare un nuovo inizio può essere tanto pericoloso quanto l'adesione cieca alla tradizione; per usare altre parole, l'amnesia è tanto problematica quanto la nostalgia. Il rientro di Gramsci in Italia tramite gli studi postcoloniali può essere inteso come un ritorno solo se si tratta il passato «come un altro paese», per riprendere un'espressione dello storico inglese Eric Hobsbawm. L'intervento di Spivak pone comunque domande importanti non solo a proposito di Gramsci ma in relazione a tutta la politica moderna che, analogamente a Gramsci, è stata dichiarata morta. Come teorici politici abbiamo infatti la responsibilità di riconsiderare la politica moderna e decidere quanto di quel passato dobbiamo tenerci? O la situazione è rovesciata come per quelli a cui nel Sud del mondo è capitato di leggere Gramsci? Nel senso che non sono loro o noi a scegliere l'eredità ma è l'eredità, tramite i conflitti a cui partecipiamo, che ci sceglie?